building snaildb 🐌 : embedded, persistent key-value store written in rust

· 16 min read

i decided to experiment with building a key-value store in rust as a fun project to both learn the language and dive into writing the low-level data structures and algorithms used in databases. inspiration was to see how far i could push the limits of a kv store compared to existing solutions like rocksdb and leveldb, especially after reading up on architectural concepts like bare-metal designs, object storage-based databases, and the bf-tree paper. this project is my way of getting hands-on experience and satisfying my curiosity about database internals, might turn out to be production ready db in future. (start date: 02 december 2025, not really sure when this gets finished)

im going to follow the first and lean principles to build this. starting off with a very simple kv store which can perform just writes with persistent storage on top of lsm tree. figuring out the actual goal of this project, as its getting very chaotic to move forward with the implementation as i kept reading a lot of papers and internals of existing dbs. so here are functional requirements, i wanted to achieve with this kv store:

- durable, crash safe kv store

- operations : write, read, delete, create db, close db

- efficient on-disk storage, and reads

- compaction strategy

also, setting the non-requirements helps me deprioritize some features, which are not required for now:

- no transactions

- no multi-process concurrent support

- no replication or distributed support

- not replacement for existing dbs with real workloads (yet, will achieve this in future)

a small note, this blog doesnt include details around the server implementation on top of the kv store.

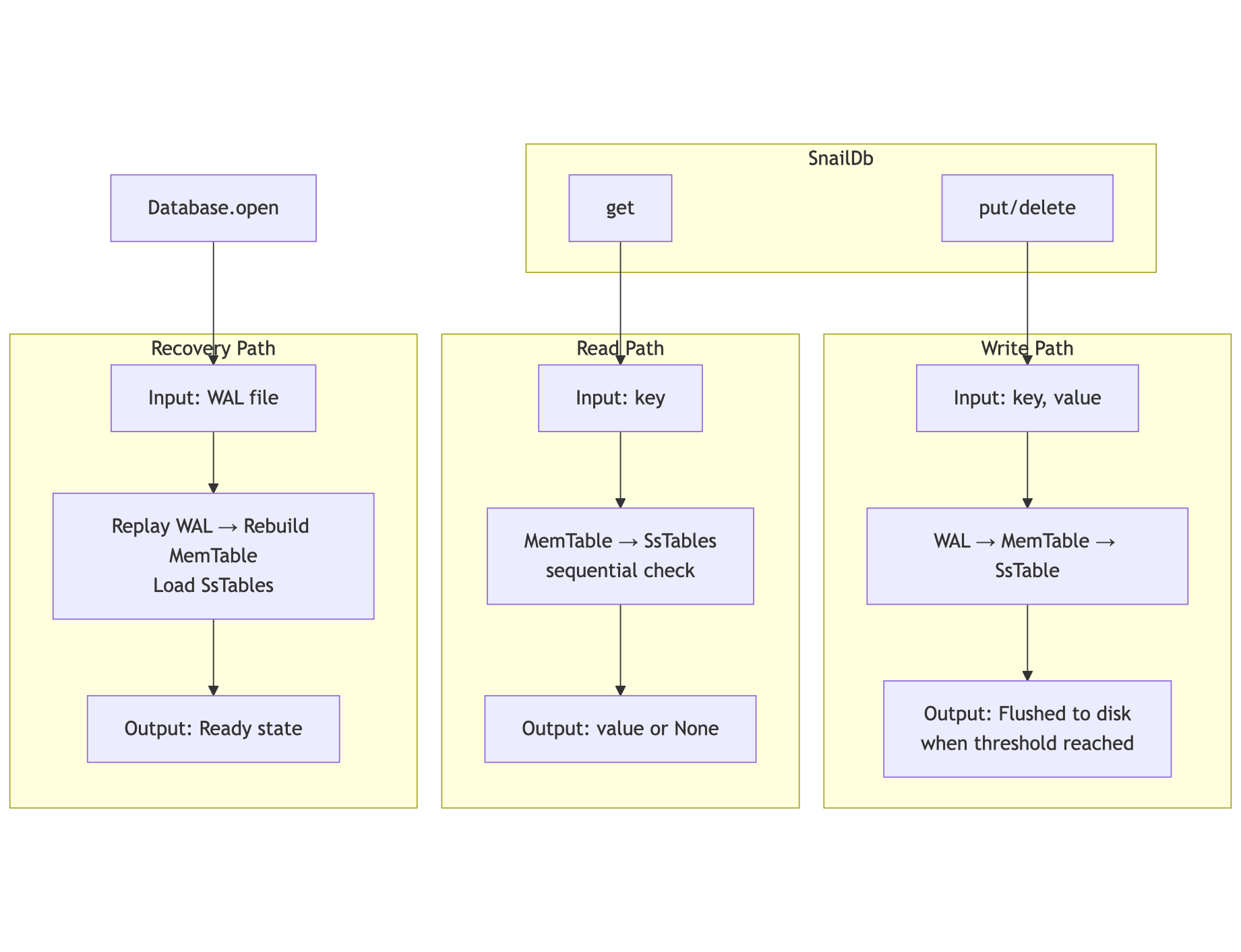

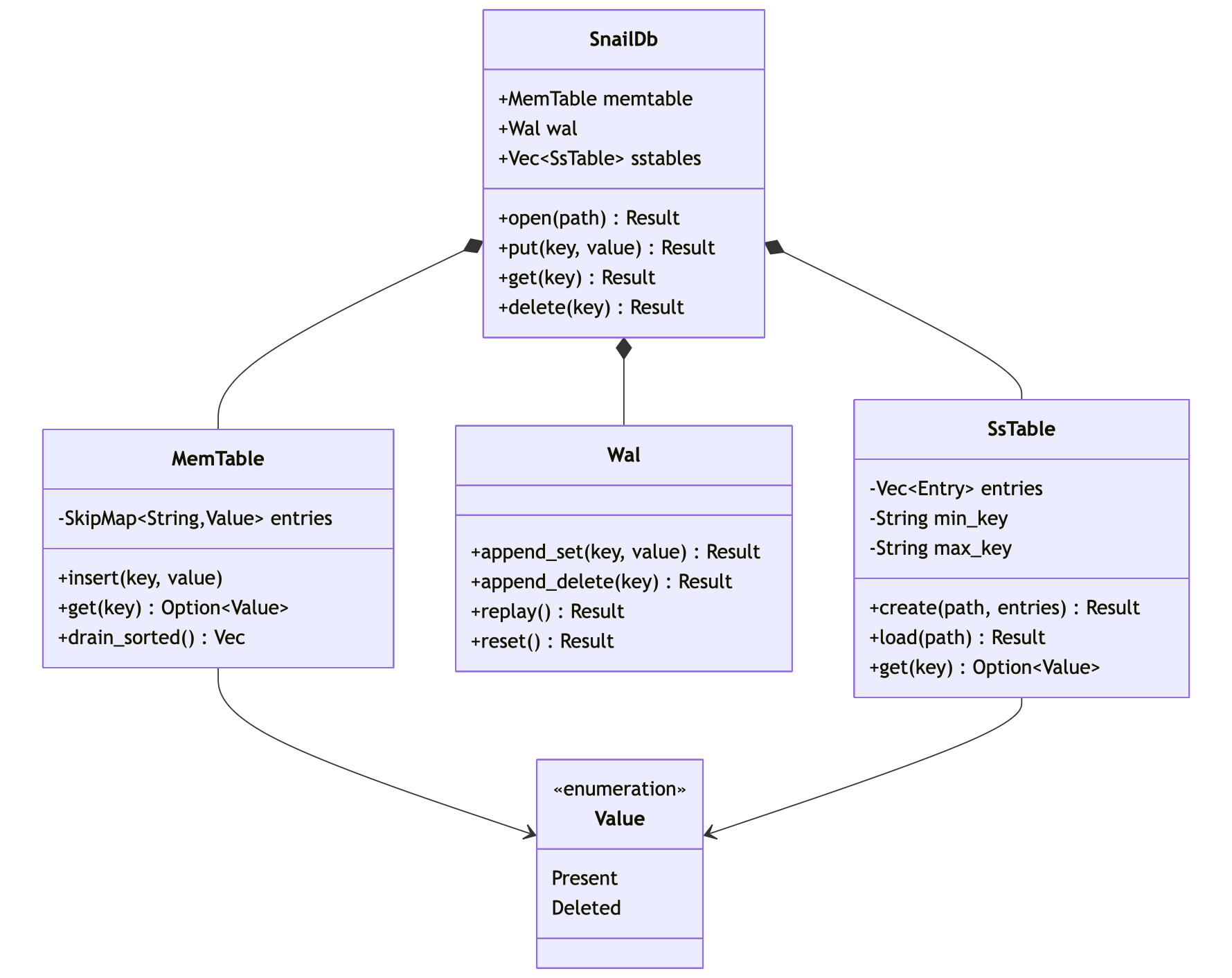

architecture (lean) #

designed a very lean architecture, with only the core components needed to build the kv store which can perform - writes, reads, deletes. no compaction, no memory management, no compression, no optimisations of reads yet.

i won’t go into a full deep dive on lsm tree structures here, that information is widely available, but i will walk through how i built some of the key components of this kv store, along with the insights and lessons learnt along the way. btw, this is my first ever project in rust, so please feel free to share your thoughts and feedback.

wal implementation #

wal is write ahead log, which is very simple, you just need to log each and every write/update/delete operation to a file, and then flush it to disk for durability. so the structure of the wal is very crucial for durability and recovery, because of potential changes in the data corruption.

once user calls db.put("user:1", "hrushikesh"), the wal will log the following record:

wal.log

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ File Offset: 0x0000 │

│ │

│ Record Header: │

│ length (4 bytes): 0x12 0x00 0x00 0x00 → 18 bytes │

│ crc32 (4 bytes): 0xAB 0xCD 0xEF ... → payload sum │

│ │

│ Record Payload (18 bytes): │

│ kind (1 byte): 0x01 → Set │

│ key_len (varint): 0x06 → 6 bytes │

│ key (6 bytes): 0x75 0x73 0x65 0x72 0x3A 0x31 │

│ → "user:1" │

│ value_len (varint): 0x0A → 10 bytes │

│ value (10 bytes): 0x68 0x72 0x75 0x73 0x68 0x69 │

│ 0x6B 0x65 0x73 0x68 │

│ → "hrushikesh" │

│ │

│ Total Record Size: 26 bytes (4 + 4 + 18) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

memtable #

memtable is in-memory data structure, which is used to store the data before it is flushed to disk (hot cache to reduce disk i/o).

SkipMap (MemTable Entry: In-Memory)

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Key (String): │

│ pointer: 0x7f8a1c002200 │

│ length: 6 bytes │

│ capacity: 6 bytes │

│ content: [0x75, 0x73, 0x65, 0x72, 0x3A, 0x31] │

│ → "user:1" │

│ │

│ Value (Value::Present(Vec<u8>)): │

│ enum discriminant: Present (0) │

│ Vec pointer: 0x7f8a1c002300 │

│ Vec length: 10 bytes │

│ Vec capacity: 10 bytes │

│ content: [0x68, 0x72, 0x75, 0x73, │

│ 0x68, 0x69, 0x6B, 0x65, │

│ 0x73, 0x68] │

│ → "hrushikesh" │

│ │

│ SkipList structure: │

│ Level 0: → [user:1] → [user:2] → ... │

│ Level 1: → [user:1] → [user:3] → ... │

│ Level 2: → [user:1] → ... │

│ (multiple levels for O(log n) lookup) │

│ │

│ Size Tracking: │

│ size_bytes: Cell<usize> = 56 │

│ (6 + 10 + 40 overhead) │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

at this point, we load all sstables (sorted strings table) into memory, and then perform the reads, which is not efficient, but a good learning point for me to also worry about the memory usage and optimisations as we bring in benchmarks, but was not a p(-1).

mutex vs mpsc #

problem - “many threads wants to append logs to a file, mainly at WAL”, when multiple client threads call db.put(), they all need to write to the WAL file

rules:

- when updating files, they must not be corrupted

- order matters

- writing is slow

one learning i had was, how to handle trade-offs between different approaches. so started understanding a little more about the difference and also taking a step back to really solve the problem not just implementing fancy things.

so, when client threads wants to write new data into the db, from multiple threads, we need to ensure that the writes are atomic, consistent and mainly in order so we dont hit any race conditions while reading the data. so, for anyone to write to the file, obvious choice would be to lock the file for each thread and then write to the file (which is mutex).

mostly, everyone can touch the file, but only once at a time.

Thread A ─┐

Thread B ─┼──> Mutex<File>

Thread C ─┘

the problem is solved, but what if there are many threads want to write to the same file, and some threads take more time than others? which can lead to deadlock, and delays other threads to perform the task. the problems that can happen with mutex are:

- contention

- long lock hold times

- hidden performance cliffs

- hard to reason about ordering of writes

so, the next option we have is to use the mpsc (which is multi-producer single consumer) channel. the mental model is - “only one thread owns the file, others send requests to the channel.”

Threads -> Queue -> File Owner thread

interesting concepts with mpsc are, the receiver thread is blocked until the 2 conditions are met:

- are there any messages in the channel?

- is atleast one sender is still alive?

case 1 #

senders alive? YES

messages? NO

if no messages, but sender is still alive, the receiver thread is blocked, “waiting for work” state.

case 2 #

senders alive? YES (doesnt matter)

messages? YES

messages exist. the reciever continues to read and process the messages until the channel is closed.

case 3 #

senders alive? NO

messages? NO

no messages, and no sender is alive. the receiver thread is unblocked, and returns a Err(RecvError) if using recv(), or ends if using rx.iter() -> worker can shutdown cleanly.

use std::sync::mpsc::channel;

use std::thread;

fn main() {

let (tx, rx) = channel();

let worker =thread::spawn(move || {

for msg in rx.iter() {

println!("worker writing... {}", msg);

}

});

tx.send("Set 1:2").unwrap();

tx.send("Set 2:3").unwrap();

tx.send("Set 3:4").unwrap();

worker.join().unwrap(); // wait for the worker thread to finish

// because we are not dropping the tx, the worker thread will keep running until the channel is dropped.

println!("channel closed");

}

which returns, as the main is blocked until the worker thread is finished, so never reaches the println!("channel closed"); line - which is case 1.

worker writing... Set 1:2

worker writing... Set 2:3

worker writing... Set 3:4

there are other methods to handle this condition, we can use try_recv() or recv_timeout() if need non-blocking or timeouts, which exit the thread, if no messages are available irrespective of sender’s state.

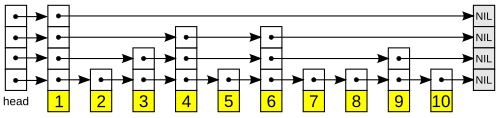

a few decisions i took very early on, after reading a few database papers and also some study on the performance of existing dbs, moving from b+tree (rust’s default btreemap) to skip list for the memtable helped me gain better write performance.

but why skip list?

skip lists (sorted linked list with multiple levels of pointers, allowing for efficient reads and writes) allow multiple threads to write simultaneously without blocking each other, while traditional tree structures (b+tree) require requires &mut self, which would necessitate Mutex or RwLock wrappers, introducing lock contention and serialization bottlenecks, that can slow down concurrent operations. since, i want to build a db that is designed for write-heavy workloads and the MemTable handles all writes before they’re flushed to disk, having a data structure that performs well under concurrent writes is crucial for overall performance.

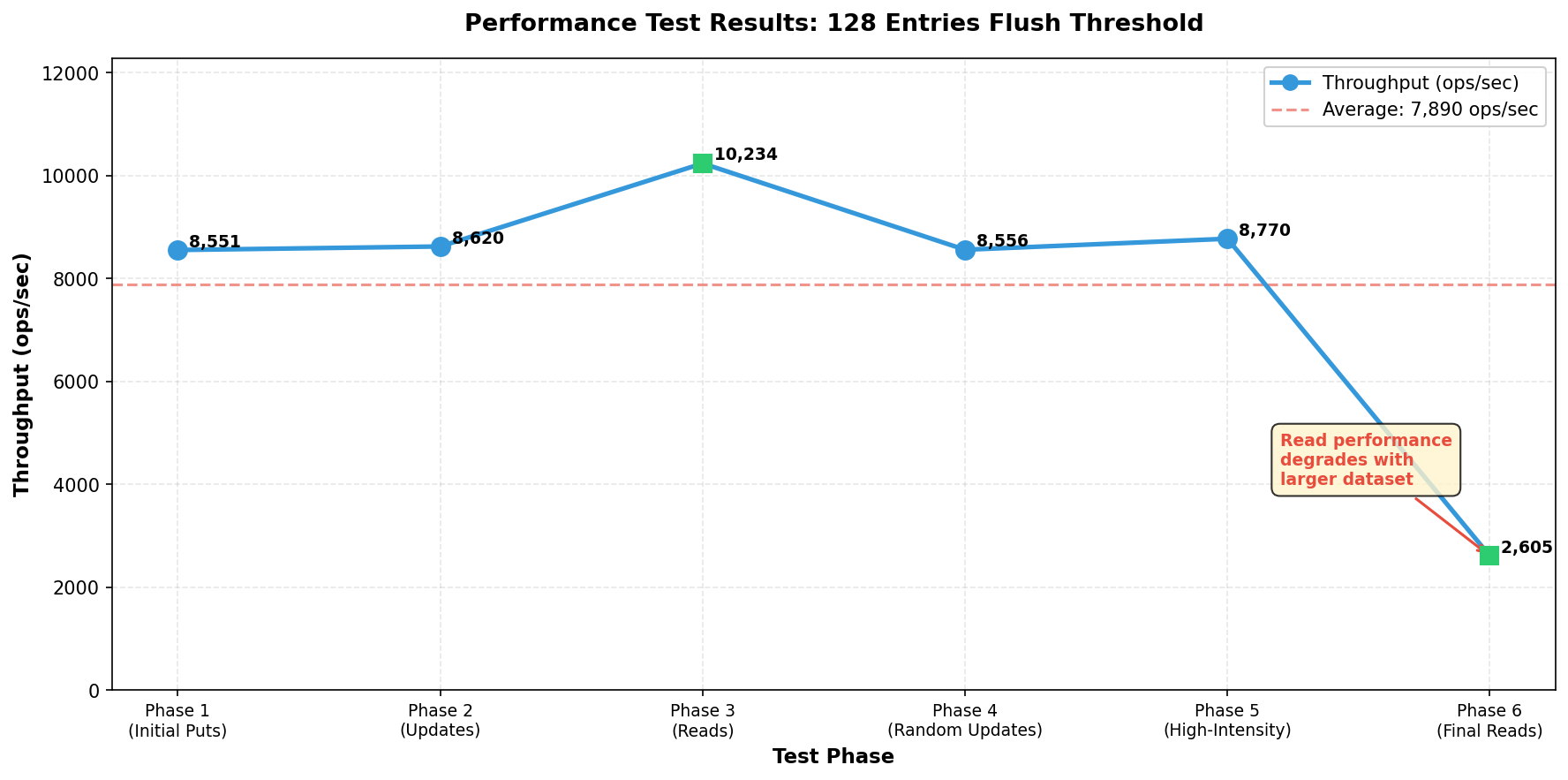

now that, the simple key-value store is built with default flush threshold of 128 entries (i dont know why 128, but its a good starting point), started to stress test the db with 100000 and 200000 entries with random writes and reads (running on mac m4 pro 16gb ram).

initial performance results (very poor, but a good learning point) #

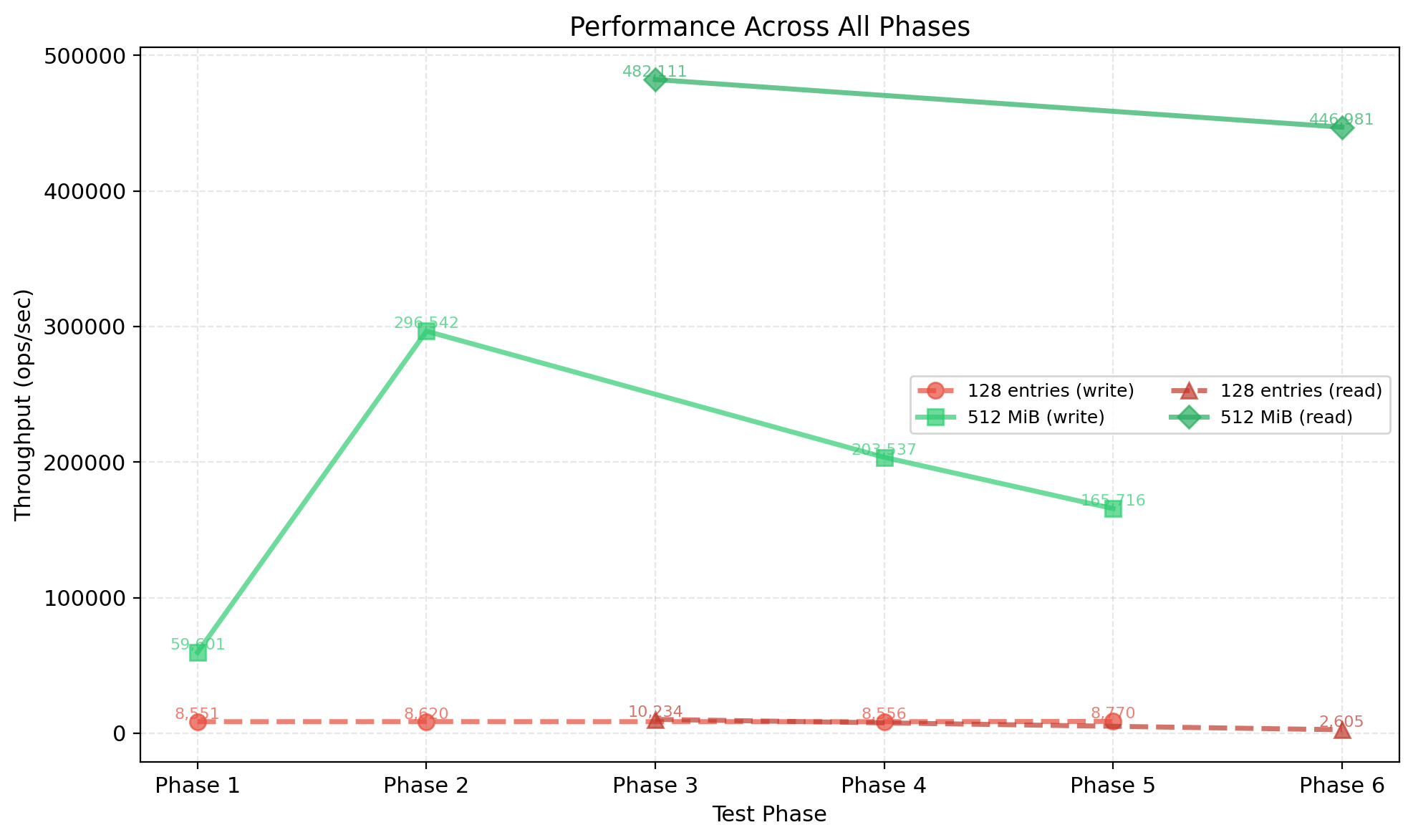

the initial tests revealed consistent write throughput of ~8,500–8,800 ops/sec across all phases. read performance showed degradation as the dataset grew: starting at ~10,000 ops/sec for a small database and dropping to ~2,600 ops/sec for a large database. while the system maintained 100% data integrity throughout all tests, the performance plateau suggested bottlenecks in several areas:

- lsm tree write path operations

- i/o operations (frequent disk syncs)

- excessive memtable flush frequency

the problem with entry-based flushing #

the 128-entry threshold had a fundamental flaw: it treated all entries equally, regardless of their actual size. this led to unpredictable and suboptimal behavior:

- a memtable with 128 large values (e.g., 1MB each) would consume ~128MB before flushing

- a memtable with 128 small values (e.g., 100 bytes each) would flush after only ~12KB

this inconsistency caused:

- non-predictable memory usage — impossible to estimate memory consumption based on entry count

- suboptimal flush frequency — small entries triggered frequent, expensive flushes while large entries delayed necessary flushes

- poor cache locality — frequent small flushes reduced the effectiveness of in-memory operations

evolution to size-based flushing #

refactored the memtable implementation to track approximate size in bytes rather than entry count. the new implementation:

- tracks entry size - calculates size for each entry (key + value + overhead)

- handles updates correctly - calculates net size changes when values are updated

- flushes on size threshold - triggers flush when memtable reaches a configurable size limit (default: 64 MiB)

this change represents a fundamental shift from counting entries to managing memory usage directly, providing predictable behavior regardless of entry size distribution.

performance improvements #

testing with a 512 MiB (but this number is not ideal for any instance of the db. rocksdb, leveldb use 64, 128 Mib as default) flush threshold showed dramatic improvements:

write throughput #

- before: ~8,500 ops/sec (consistent across all phases)

- after: Up to ~296,000 ops/sec for updates

- improvement: 35x faster for update operations

read throughput #

- before: ~2,600 ops/sec (degraded performance on large datasets)

- after: ~446,000 ops/sec for final verification reads

- improvement: 171x faster for read operations

warm-up effect #

performance demonstrated a clear warm-up pattern, starting at ~9K ops/sec as the memtable began filling, ramping up to ~60K ops/sec as the memtable approached capacity, and reaching peak performance of ~296K ops/sec once fully warmed up. the larger memtable provides several key benefits: reduced flush frequency with fewer expensive I/O operations (sync_all() calls), improved cache locality as more data stays in memory longer, and sustained high throughput maintaining 165K+ ops/sec even under sustained load (200K+ operations).

trade-offs and configuration #

while larger flush thresholds improve throughput, they also introduce trade-offs:

- increased memory usage - larger memtables consume more RAM

- longer WAL replay time - more data to replay during recovery

- higher latency spikes - larger flushes can cause brief pauses

the 64 MiB default provides a good balance for most workloads, but users can tune this based on their specific requirements using with_flush_threshold(bytes). for write-heavy workloads with sufficient memory, larger thresholds (128 MiB+) can provide significant performance gains. for memory-constrained environments or latency-sensitive applications, smaller thresholds may be more appropriate.

why? because, the larger flush threshold meant, the memtable is larger and has more levels in the skiplist, which is mathematically proven below:

128 MiB memtable with 64 B values:

└── Up to 2M keys in skiplist

└── Skiplist height: ~21 levels

512 MiB memtable with 64 B values:

└── Up to 8M keys in skiplist

└── Skiplist height: ~23 levels

└── Slightly more pointer chasing per insert

the trade-offs here can be:

Small memtable (128 MiB):

- ✔ Faster per-operation (shorter skiplist)

- ✔ Less memory usage

- ✘ More frequent flushes

- ✘ More SSTables created → more compaction work

Large memtable (512 MiB):

- ✘ Slower per-operation (taller skiplist)

- ✘ More memory usage

- ✔ Fewer flushes

- ✔ Better batching for large values

a few of the reasons many databases keep the memtable flush threshold small and me defaulting to 64 Mib. because, im not already worried or you can say not aware (at the moment) of how writes perform with compaction, mainly with smaller flush threshold, i was more leaning towards smaller memtable to achieve better memory management for now.

read optimisations #

ideally, i want to build the production grade bloom filter for each sstable, to efficiently skip the reads of each sstable if the key is not present. but, while learning a lot of things, i approched this very lean, as an intermediate step i implemented a simple footer for each sstable to store the min_key and max_key, you may ask me why? as the keys are already stored sorted in sstable (as the name says sorted strings table), we can perform string comparison to check if the key is within the range of the sstable.

if key < min_key or key > max_key, skip the sstable

this small optimisation gained me more than 4x in read performance, at scale as we are skipping most of the sstables without reading entire file. also to call out, we use binary search to find the key in the sstable, so the worst case time complexity is O(log n) for each sstable, but at the db level its still n * O(log n), where n is the number of sstables (without footer optimisation).

here starts the journey of read optimisations for snaildb, where i now start to understand the working of bloom filters and how efficient are they for incredibly fast lookups in very large datasets. which will now remove the logic of loading the sstables into memory, and only load the bloom filter of each in-memory.

2 things to figure out, when building a bloom filter:

- how many hash functions (k)?

- how many bits per key (m)?

optimal number of hash funcs, k = ceil(-ln(error_rate)/ln(2))

so the calculations are simple, for:

- error_rate = 0.01 (1% false positive rate)

k = ceil(-ln(0.01)/ln(2))

k = ceil(-(-4.605)/0.693) -> ceil(6.64) = 7 hash functions

similarly for 0.1% error rate, it comes out to be 10 hash functions. not extending this explanation of calculation, but my intent is to show how to calculate and most of the databases bare 1% error rate, so default its set to 7 hash functions. we got the answer for k, now for the bits per key (m).

to achieve error rate

f, you need enough bits so that when optimally filled (50% ones, 50% zeros) with the optimal number of hash functions, the probability ofkrandom positions all being 1 equalsf.

bits_per_key = -ln(error_rate)/ ln(2)^2

bits_per_key = -ln(0.01)/ ln(2)^2

bits_per_key = -(-4.605)/ 0.693^2

bits_per_key = 9.99 -> 10 bits per key

so, for 1% error rate, we need 10 bits per key. the reason behind me chosing 10 bits per key is, to keep the bloom filter size small, and also to keep the false positive rate low (which is 1%, and its a trade-off i was willing to take), might comeback to this later.

the struct for the bloom filter is:

pub struct BloomFilter {

bits: Vec<u8>,

}

impl BloomFilter {

const NUM_HAS_FUNCTIONS: usize = 7;

const BITS_PER_KEY: usize = 10;

const DEFAULT_ERROR_RATE: f64 = 0.01; // 1% error rate

}

you can read more about the bloom filters here.

Reads are 2-3x faster than writes (expected for LSM):

Size │ Writes │ Reads │ Ratio

────────┼────────────┼────────────┼───────

64 B │ 1.38M │ 3.86M │ 2.8x

256 B │ 1.30M │ 3.24M │ 2.5x

1 KB │ 815K │ 1.98M │ 2.4x

4 KB │ 367K │ 1.14M │ 3.1x

16 KB │ 31K │ 740K │ 24x ← Bloom filter huge impact here

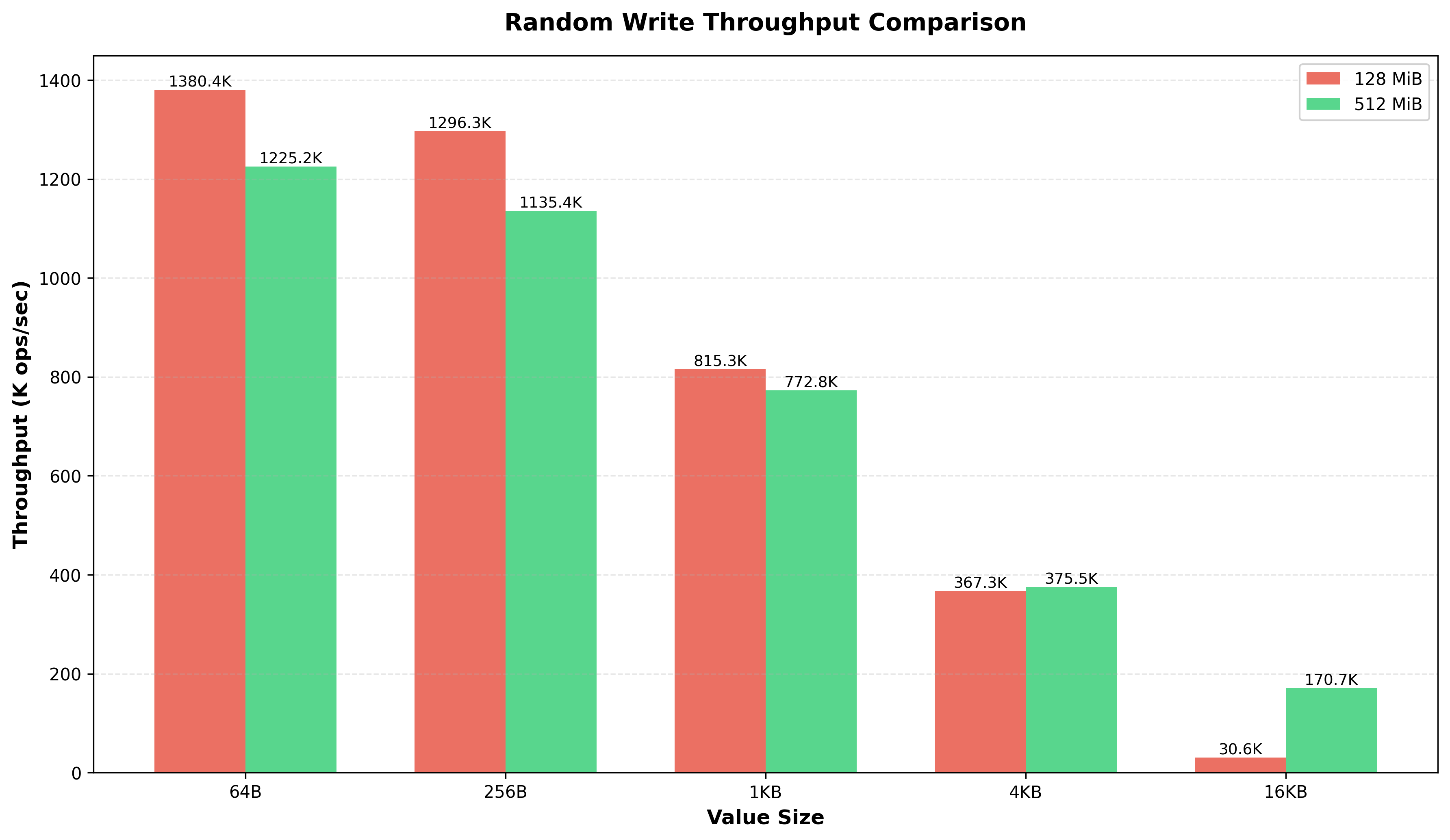

a few observations here, when i was testing the read performance with different size of flush thresholds, 128, 512 Mib. the numbers were slightly lower for the larger threshold, you can see in the below graph:

benchmarks #

ops/sec by value size #

measures how many read/write operations snaildb can perform per second across different value sizes (64 B to 16 KB) and flush thresholds (128 MiB vs 512 MiB). smaller values = more ops/sec; larger memtables slightly reduce throughput due to taller skiplists.

throughput (512 MiB threshold) #

measures raw data throughput (GB/s) for reads and writes at the 512 MiB flush threshold. while ops/sec drops for larger values, actual data throughput increases - reaching ~10 GB/s for 16 KB reads. this shows the db scales well for bulk data transfer.

snaildb vs rocksdb vs leveldb #

benchmarked snaildb against rocksdb and leveldb to understand where we stand. the results reveal snaildb as a read-optimized store, writes are slower than expected (at the moment, but i want it to be more write heavy in future), but reads dominate at larger value sizes.

random writes #

measures write throughput (K ops/sec) for random key insertion across value sizes. tests how efficiently each db handles the memtable → WAL → flush pipeline.

snaildb is 2-2.5× slower for small writes (64–256 B), but catches up at 4 KB. the gap is likely due to WAL sync behavior—rocksdb/leveldb batch syncs by default while in snaildb, we are syncing more aggressively.

random reads #

measures read throughput (K ops/sec) for random key lookups. tests bloom filter efficiency, sstable scanning, and in-memory cache behavior across value sizes.

this is where snaildb excels. at 4 KB values, snaildb is 20× faster than rocksdb and 31× faster than leveldb. the bloom filter and simpler read path pay off massively as value sizes grow.

read speedup vs rocksdb #

shows how much faster snaildb reads are compared to rocksdb at each value size. the multiplier grows dramatically with larger values - 20× faster at 4 KB.

current status: snaildb is a read-optimized, for read-heavy workloads (especially with larger values), it significantly outperforms rocksdb and leveldb. on the write side, we are not as fast as rocksdb and leveldb, but we are still in the ballpark, might need to revisit this later.

future: im now at a good state to start building the compaction layer and the range queries support for the snaildb. im sure about the current writes, reads performance, and also the memory usage is under control. we already beat existing kv stores in the market in terms of writes and reads performance. once the compaction layer is ready, i can focus on real workloads and performance benchmarks with other dbs, and make it completely open source and production ready.

how to use snaildb? #

use snaildb::SnailDb;

use anyhow::Result;

fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Open or create a database at a directory

let mut db = SnailDb::open("./data")?;

// Store a key-value pair

db.put("user:1", b"Alice")?;

db.put("user:2", b"Bob")?;

// Retrieve a value

match db.get("user:1")? {

Some(value) => println!("Found: {:?}", String::from_utf8_lossy(&value)),

None => println!("Key not found"),

}

// Delete a key

db.delete("user:2")?;

Ok(())

}

there are more examples here.

the official handles:

thanks for reading! happy 2026 🌄!